LIPEDEMA: DESCRIPTION, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Content extracted from the book “Victory Against Cellulite” by Dr Roberto Chacur, Ed. AGE, 2023.

Dr. Fernanda Federico Rezende

Dr. Roberto Chacur

Lipedema is an inflammatory vascular disease characterized by the abnormal deposit of fat, especially in the subcutaneous tissues of the hips, buttocks and lower limbs, in a chronic, progressive form and with a strong hereditary character. Lipedema can also occur in the upper limbs, but its presence is not as common as in the lower limbs.

This clinical condition may include pain, swelling and sensitivity to touch in the affected areas. When left untreated, lipedema, in more advanced stages, can progress to affect the lymphatic and vascular systems, causing deformities, reduced mobility and chronic pain in the

lower limbs.

Lipedema was first described in 1940 by cardiovascular surgeons Dr. Edgar Allen and Dr. Edgar Hines at the Mayo Clinic. They described it as a deposit of fat in the subcutaneous tissues of the buttocks and lower limbs accompanied by orthostatic edema. Despite having been described over 80 years ago, lipedema is still poorly diagnosed and treated in Brazil and worldwide, so much so that it was only in 2022 that the pathology was included in the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), EF 02.2 Lipedema, BD93.1e Lipolymphedema (DUDEK; Białaszek; GabrieL, 2021).

See Chapters

CHAPTER 1 - DEFINITION, HISTORY AND NOMENCLATURE

CHAPTER 2 - ONLINE QUESTIONNAIRE FOR CELLULITE CLASSIFICATION

CHAPTER 3 - LIPEDEMA: DESCRIPTION, DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

CHAPTER 4 - ANATOMY OF THE GLUTE REGION APPLIED IN PRACTICE

CHAPTER 6 - INJECTABLE CELLULITE TREATMENTS

CHAPTER 7 - LASER-LIPO: INVASIVE TECHNOLOGY

CHAPTER 8 - OTHER CELLULITE TREATMENTS

CHAPTER 9 - BIOSTIMULATORY EFFECTS OF MICROSPHERE INJECTIONS INTO OVERLYING SKIN STRUCTURES

CHAPTER 10 - INFLUENCE OF HORMONES ON CELLULITE: WITH EMPHASIS ON ADIPONECTIN

CHAPTER 11 - GOLDINCISION®: A MULTIFACTORIAL APPROACH TO THE TREATMENT OF CELLULITE

CHAPTER 12 - STAINS POST-GOLDINCISION®

CHAPTER 13 - ADVERSE EFFECTS AND COMPLICATIONS IN GOLDINCISION®

With the collaboration of experienced medical professionals, Dr. Roberto Chacur brings together in this book an approach around the theme ranging from the genesis of cellulite, the proper method of evaluating and classifying, associated diseases and hormonal modulation to existing treatments, what really works and why the GOLDINCISION method is considered the gold standard.

Therefore, in this chapter, I will present lipedema and my experience as a vascular surgeon in the treatment of this pathology, which is still barely known in our country and is often confused with other conditions, such as lymphedema, vascular insufficiency and obesity. To this end, the chapter has eight sections. The second section presents the general characteristics of the disease. The third describes the clinical findings on lipedema. The fourth points out some of the psychological impacts of this pathology. The fifth lists its stages and types. Section six highlights the etiology and pathogenesis. Sections seven and eight discuss its diagnosis and treatment. At the end, we shall add some final considerations.

GENERAL CHARACTERISTICS

Lipedema is a disease that occurs almost exclusively among women. There are only two reports of lipedema in men in the literature (Wold, Hines, Allen, 1951; CHEN et al., 2004). It is estimated that 12.3% of women in Brazil have lipedema (Amato et al., 2022), while in Europe this rate varies between 0.06 and 39% (Fife, Maus, Carter, 2010; Schwahn-Schreiber, Marshall, 2011). The prevalence of this condition among women occurs because, compared to men (Bano, 2010), they have a greater amount of subcutaneous adipose tissue and, consequently, a greater expression of steroid hormones. Furthermore, female hormones determine a characteristic body distribution of adipose tissue in women (Van Pelt et al., 2006; Gavin, Cooper; Hickner, 2013).

The most frequent complaint presented in the medical practices is the difficulty in reducing measurements in the hips and legs, despite diet and physical exercises. Patients report constant disproportion between the upper and lower parts of the body. Despite the higher incidence in the lower limbs, lipedema may exclusively affect the arms or develop concomitantly in them and in the lower limbs. Patients who suffer from this problem have edema in the lower limbs that does not improve even with night rest, a fact that characterizes the enlargement of the limbs due to the deposit of fat and not the accumulation of liquids therein.

Furthermore, many patients complain of pain when touching their legs, especially on the sides of the thighs, in addition to the appearance of spontaneous ecchymoses. They also complain of irregularities in the legs and buttocks, with the presence of cellulite (with the oft-reported technical name of gynoid lipodystrophy). Many report palpating nodules on the legs, described as being similar to bags of peas, beans or Styrofoam balls (Meier-Vollrath; Schmeller, 2004). Approximately 50% of patients with lipedema are obese (Wold, Hines, Allen, 1951; Harwood, 1996), a fact that makes diagnosis difficult and may delay adequate treatment. By the way, in obesity, the distribution of body fat is more homogeneous throughout the body, with no reports of pain and frequent bruises. However, obese patients and patients with lipedema present an increase in the severity of symptoms and reduced mobility. In my experience, fatigue, muscle weakness and difficulty achieving muscle hypertrophy are symptoms that have been reported by patients.

Lipedema often develops at the onset of puberty and worsens during periods of hormonal fluctuations, such as use of oral contraceptives, pregnancy, menopause, and hormone replacements (Meier-Vollrath, Schmeller, 2004). Unfortunately, patients only seek medical treatment

when the disease is already in more advanced stages. To make matters worse, there are multiple reports of countless frustrated attempts to lose body measurements through restrictive diets, high-impact physical exercises, muscle hypertrophy with high loads and various treatments for fibrosis and localized fat. Many report one or more liposuctions on the legs and hips, with subsequent recurrence of the disease and worsening of the fibrosis, especially on the hips.

When patients are asked if they have a family member with a similar condition, most answers are positive. Studies present estimates between 16 and 64% with self-reported positive family history. This fact suggests a strong hereditary nature of lipedema (Suga, 2009; Herbst, 2012; Rudkin, 1994).

CLINICAL FINDINGS

The main characteristic of lipedema is the presence of symmetrical and bilateral widening of the lower limbs, sparing the feet. This characteristic is important to differentiate lipedema from obesity. The feet are affected in cases of obesity; not in lipedema. Thus, patients with lipedema have lower limbs that look like pantaloons or baggy pants, and it is possible to visualize a step between the ankles and the feet, where fat deposits usually cease (Hild et al., 2010). Another feature of note is the formation of adipose pads anteriorly to the lateral malleoli and the effacement, due to lipid deposits, of the grooves of the retromalleolar muscles.

There is no darkening or thickening of the skin (Langendoen, 2009), except when lipedema is accompanied by lymphedema or venous insufficiency. Often, patients have pain when palpating the affected areas, especially on the sides of the thighs and ankles. They also report worsening pain in menstrual periods (Woodliffe, 2013). The Godet sign is absent. In addition, punctiform ecchymoses along the lower limbs are common, with no history of known trauma and telangiectasias on the sides of the thighs (Ourke, Langford, White, 2015).

Cases of lipedema developed exclusively on the arms are very rare. This type of lipedema more often affects not only the arms, but also the pelvis, forearms and, simultaneously, the lower limbs. In a study with 144 patients (Herpertz, 1997), it was found that 31% of patients have lipedema in the lower limbs and arms and only 3% exclusively in the arms.

As the disease progresses, fat pads are formed medial to the knees, causing the feet to move apart, which compensates for the medial unevenness of the knees. This characteristic, if progressively worsened, causes a significant reduction patient mobility (Stutz, Krahl, 2009).

Another common feature of lipedema is pain complaints, which have led to lipedema being known as the painful fat syndrome (Allen, Hines, 1940). In this sense, common complaints are pain upon digital pressure, heaviness and discomfort. There are often complaints of mild to moderate edema with little improvement when raising the lower limbs, but with significant improvement of pain symptoms with rest. A study (Schmeller, Meier-Vollrath, 2008) with 50 patients with stage II lipedema showed that the levels of pain reported by these women were similar to those of patients with chronic pain. In this study, Schmeller and Meier-Vollrath (2008) reported that the way patients with lipedema most intensely referred to pain was with words like “heavy, exhausting, extenuating, violent”. This suggests a more impactful pain condition in the lives of patients with lipedema.

PSYCHOLOGICAL IMPACTS OF LIPEDEMA

Patients with lipedema are often considered fat, as well as suffering from misdiagnoses such as lymphedema and chronic venous insufficiency. These incorrect diagnoses lead to failed treatments and generate anguish and frustration in them. Many undergo extremely restricted diets, use diuretics excessively, undergo high-intensity physical exercises and still fail to lose measurements in their legs.

Many others are unnecessarily subjected to varicose vein surgery. Several do not tolerate the compression therapies indicated for chronic venous insufficiency and lymphedema. As if that weren’t enough, I often see in my practice patients with lipedema without a previous diagnosis and who have already undergone numerous liposuctions, with unsatisfactory results. They present deep fibrosis and disease recurrence shortly after the procedures.

These patients also report difficulty wearing long boots. They also often wear different sized clothes, small (S) on the upper body and medium (M) or large (L) on the lower body. They say they dream of wearing shorts, but they don’t because of fibrosis and irregularities in the thighs.

The frustration and judgment of people who are unaware of the disease lead these patients to develop bulimia nervosa, anorexia and pseudo Bartter syndrome (Foldi E., Foldi M., 2006). These women need to be welcomed and heard; as such, it is often necessary to indicate adjuvant psychotherapy.

STAGES OF LIPEDEMA

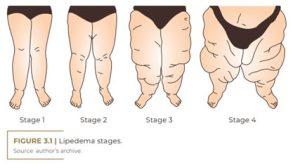

Lipedema is classified into stages, ranging from I, II, III to IV, according to the severity of the disease. This staging proposed by Meier-Vollrath and Schmeller (2004) classifies the severity of the disease. Stage I is described as normal skin with enlarged hypodermis. In stage II, there are irregularities in the skin and adipose tissue, with the formation of large mounds of unencapsulated tissue. Stage III includes thickening and hardening of the subcutaneous tissue, the presence of nodules and the formation of large, visible, protruding fat pads, especially on the thighs and around the knees.

Stage IV is the most advanced stage of the disease, with the presence of lymphedema associated with lipedema, referred to as lympholipidema. However, the categorization of stages by Meier-Vollrath and Schmeller (2004) does not provide a prognosis of evolution to lipolymphedema. This stage can progress gradually or suddenly (Fife, Carter, 2009). In this sense, although not yet specified, many factors can be triggers for the development of secondary lymphedema, the main and most common of which being obesity.

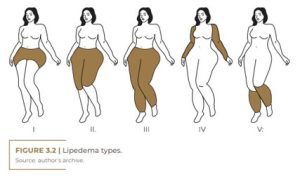

Lipedema can be classified according to the area of involvement in the body. There are five different types of fat deposit patterns. Some patients can be classified into more than one type. Type 1 affects the pelvis, glutes, and hips. Type 2, on the other hand, reaches from the glutes to the knees, with a protrusion of folded fat on the inside of the knee. Type 3 involves the region from the glutes to the ankles, while type 4 affects only the arms. Finally, type 5 affects only the lower leg.

Földi E. and Földi M. (2006) indicate two main lipedema phenotypes: columnar and lobar. The first, and most common, is characterized by increased proportions of the lower extremities with sequential conical irregularities. The lobar phenotype is rarer and is characterized by the presence of large fat protuberances that fold over the hips, lower limbs and sometimes even the upper portions of the arms.

ETIOLOGY AND PATHOGENESIS

The etiopathogenesis of lipedema is still unclear. In this regard, several theories have been conjectured; one of them relates the development of lipedema to a disorder of the female hormonal axis. Lipedema develops at the beginning of puberty (Mayes, Watson, 2004), when estrogen acts on adipose tissues through estrogen receptors (Herbst et al., 2015). Thus, it is believed that estrogen may play an important role in the formation of adipose tissue and other tissues that have estrogen receptors (Shin et al., 2011). Therefore, a possible change in the pattern of estrogen receptors and even a failure in central responsiveness may explain the abnormal distribution of fat in individuals predisposed to this condition, as well as the difficulty that patients with lipedema have in losing gynecoid and arm fat (Herbst, 2012).

Another theory, studied by Földi M. and Földi E. (2006), suggested that microangiopathy in fatty tissue increases capillary permeability and consequently increases protein leakage, causing capillary fragility and increased ecchymosis. The authors also observed that the decrease in the venoarterial reflex, present in lipedema, is associated with an increase in the formation of ecchymoses and bruises (Szolnoky et al., 2008). Thus, the tissue hypoxia present in lipedema induces angiogenesis, which is considered pathological due to the fragility of these newly formed capillaries. As vascular endothelial growth factor is one of the elements that control angiogenesis, abnormally high levels of this growth factor are found in lipedema (Frank, 1994). High levels of malonyl dialdehyde and carbonyl proteins (Zhao et al., 2003) were found in chronically inflamed adipocytes, which demonstrates chronic oxidative stress and accelerated lipid peroxidation in lipedematous tissues (Knudsen, 2008).

Suga et al. (2009) demonstrated that lipedematous tissue has adipocytes of more varied shapes, that is, larger and surrounded by macrophages, compared to normal adipose tissues. The authors also used immunohistochemical studies to identify the presence of necrotic adipocytes, with the proliferation of stem cells. This situation can lead to adipogenesis, which can generate hypoxia similar to that found in the tissues of obese people, resulting in necrosis and mobilization of macrophages in these areas. CD68+ macrophages and cells positive for CD34 and KI67 have been found in necrotic adipocytes in lipedematous tissue. These results reinforce the hypothesis that the ischemic and necrotic environment with intense phagocytic activity is the result of rapid adipogenesis in lipedema tissues.

Crescenzi et al. (2018) found, through a multimodal MRI protocol in women with lipedema, that there is an increase in sodium concentration, both in adipose and muscle tissue. These high levels can be explained by inefficient vascular and lymphatic clearance or by increased sodium deposition in the chronic inflammation of lipedema. The increased levels of sodium in the muscles may explain the chronic fatigue and reduced muscle strength found in patients. The study (Crescenzi et al., 2018) also suggests that tissue sodium may be an important inflammatory marker of the disease.

A genetic etiology is strongly suggested in lipedema, with 64% of cases presenting a family history reported by female carriers of the condition (Herbst, 2012). A study in 2010 evaluated six families with more than three generations with lipedema. A pattern with autosomal dominant inheritance with incomplete penetrance limited to sex was found (Child et al., 2010).

Michelini et al. (2020) suggest that the action of aldo-keto-reduc-tase (1C1) in the regulation of steroid hormones is directly related to the accumulation of fatty tissue in the subcutaneous tissue. Results also indicate that the 1C1 gene mutation may be related to the development of lipedema due to failure to inactivate progesterone, indirectly regulating subcutaneous fat adiposity (Michelini, 2020). As a result, this is the first candidate gene to be associated with non-syndromic lipedema.

DIAGNOSIS OF LIPEDEMA

The diagnostic criteria for lipedema, according to my own experience with the disease, are:

1. Reports of inflamed adiposity (fat), forming a non-depressive edema and with symmetrical and bilateral distribution.

2. This edema occurs mainly in the lower limbs, but sparing the feet (but not the ankles).

3. Keep in mind that swollen fat is not as common in the arms, but it can happen there. In this case, however, adiposity spares the hands.

4. Edema is resistant to diet, physical exercise, and elevation of the limbs. This resistance causes the affected regions to enlarge progressively.

5. Furthermore, patients have increased sensitivity in areas with lipedema, feeling more pain when touched or when suffering mild trauma.

6. Ecchymoses may spontaneously appear, with no identified cause.

7. Reticular varicose veins, especially telangiectasias, can also be seen on the sides of the thighs.

8. In addition, there is a negative Stemmer sign.

9. Many fibroses (cellulite) are present.

10. Irregularities occur on the skin, with the appearance of an orange peel.

11. There are noticeable fat deposits around the hips, knees and ankles.

12. When feeling the patient’s skin, a certain softness, elasticity and nodulation are perceived (similar to the sensation of touching a bag with Styrofoam balls).

It is important to note that these characteristics that I have indicated based on my experience with lipedema are similar to those pointed out by other references, such as Wold, Hines and Allen (1951); Harwood et al. (1996); Meier-Vollrath and Schmeller (2004); Hild et al. (2010); and Fife, Maus, and Carter (2010).

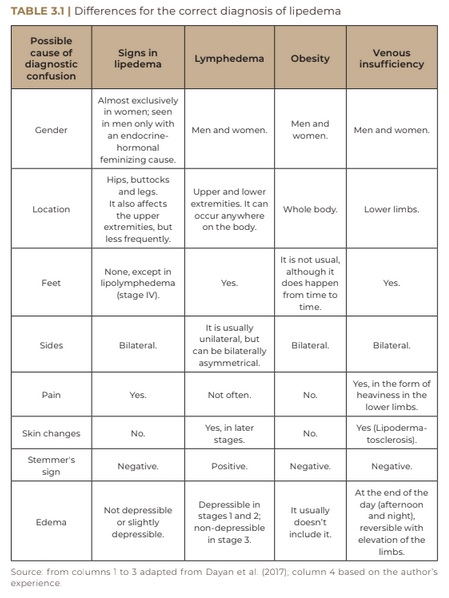

As such, it should be noted that the lack of a laboratory, genetic or imaging tests for the diagnosis of lipedema and the lack of medical familiarity with the corresponding criteria make this disease highly underreported and often mistaken for other pathologies, such as lymphedema, venous insufficiency and, more frequently, obesity. These possible confusions lead to wrong medical diagnoses, which, in turn, imply ineffective treatments, leading to frustration among patients. Therefore, I introduce in Table 3.1 the differential diagnoses of lipedema in relation to the pathologies for which it is most commonly mistaken.

In summary, the distribution of body adiposity in obesity is truncal and does not spare feet and hands. Obese patients lose weight evenly and respond well to a low-calorie diet and physical exercise (CORNELY, 2006). Lipedemic adiposity is extremely resistant to restrictive diets and physical exercises, and the adiposity of extremities is persistent.

Telangiectasias, varicose veins and thrombophlebitis can develop in patients with lipedema, but the rate of chronic venous insufficiency is low in them (Harwood et al., 1996). In my practice, I often see patients without a diagnosis of lipedema who associate the characteristic pain and edema of this condition with varicose veins. Many are submitted to surgical and sclerotherapy treatment for varicose veins and still remain symptomatic. Spontaneous ecchymoses are common and pain upon finger pressure is a frequent complaint (Wold, Hines, Allen, 1951). It is important to point out that, in chronic venous insufficiency, the edema is symmetrical, bilateral, the pain is describe to as heaviness and tiredness at the end of the day, and the edema is reversed with the elevation of the limbs.

Lymphedema is a pathology in which the lymphatic return is slow due to congenital causes or due to trauma, infections or surgeries. Lymphedema, stasis of protein-rich interstitial fluid, is mostly unilateral, involving the entire length of the affected limb, including the distal end. In the initial stages, the edema is compressible with Godet’s sign, it resolves spontaneously with elevation of the limb, and the skin is soft. In advanced stages, the edema is permanent, the skin is thicker, there are signs of inflammation, fibrosis formation and the Stemmer sign is positive (inability to form a fold when bending the dorsal region of the toes) (Fife, Carter, 2008). In patients with early-stage lipedema, edema is minimal, adiposity spares feet and hands, and Stemmer’s sign is negative. In cases of lipedema that worsen and evolve concomitantly with lymphedema, lympholipedema, the Stemmer sign is positive (Fife, Carter, 2008).

Differentiating lipedema from lymphedema in conditions such as morbid obesity or lipolymphedema can be challenging. Both overload and slow down the lymphatic system, creating chronic edema. In morbid obesity cases, edema can be due to stasis, venous insufficiency, heart failure, among other causes. Obesity can aggravate both lipedema and chronic edema. Despite the difficulty in diagnosis, the treatment of overweight and edema is essential (Helyer et al., 2010).

TREATMENT OF LIPEDEMA

Lipedema is a chronic, progressive and incurable disease. However, there are treatments that improve the symptoms and prevent the progression of the disease (if untreated, it can lead to reduced mobility and physical deformities, which generates irreversible sequelae and psychosocial impacts on the patient). Therefore, a good relationship between the doctor and the patient is very important in order for the patient to develop realistic expectations about the results of the treatment, which can often be slow. The patient needs to be aware that this is an ongoing process and that, primarily, it involves changing their lifestyle.

The treatment that I am going to indicate is based on my clinical experience with patients affected by lipedema. Its pillars are: 1) diet therapy; 2) physical exercises; 3) compression therapy; 4) lymphatic drainage; 5) nutritional supplementation and, if necessary, 6) medications; and 7) surgical treatments.

In terms of diet therapy, there is no scientific evidence that weight loss improves lipedema, but the opposite is not true: weight gain does aggravate the disease. Thus, if the patient has a normal BMI, restrictive diets are not indicated, only non-inflammatory diets. In this particular case, I recommend and have had good results with the Mediterranean diet. For patients with high and very high BMI, low-calorie diets should be prescribed, such as ketogenic and low-carb diets.

The recommended physical exercises are those of low impact, to avoid overloading joints such as the knee and ankle. Aquatic exercises have shown low impact and patients have good tolerance to them. Aerobic exercises activate venous and lymphatic circulation and improve edema – especially when there is lipolymphedema.

The recommendation for elastic compression must be individualized. The stage of lipedema and the presence or absence of chronic venous insufficiency will determine the intensity in millimeters of mercury of elastocompression. Very inflamed patients generally do not tolerate compressive therapy with elastic stockings due to pain. In this case, low compression stretch pants are recommended, as they are more comfortable. Fife, Maus and Carter (2010) have pointed out that compression therapy is the most used in Europe.

Lymphatic drainage must necessarily be prescribed in the presence of lipolymphedema. However, my experience has shown that patients with less advanced stages of lipedema who undergo drainage report physical comfort, especially relaxation and pain relief, in addition to emotional rest.

Nutritional supplementation, on the other hand, must be individualized according to the particular conditions of the patients – that is, there is no single supplementation protocol. Laboratory tests and bioimpedance help customize this pillar of treatment; for example, hypovitaminosis attested in the laboratory must be corrected by vitamin replacement. In turn, herbal medicines, whose active components will always be indicated on a case-by-case basis, help reduce the inflammation of the patient and have shown good results in my clinical experience.

Medication, on the other hand, is another individualized aspect in the treatment of lipedema and is related to the investigation of the possibility that the patient has associated comorbidities; among these, the ones that appear most in my practice are obesity, thyroid dysfunction, metabolic syndrome, iron deficiency and chronic venous insufficiency. For lipedema specifically, Reich-Schumple et al. (2017) showed that there is no indication for drug treatment. They also point out that the use of diuretics is not recommended, as it worsens the condition.

In terms of surgical treatments, liposuction is the one most used. However, it is only indicated when patients have therapeutic failure in clinical treatment or when they have mobility restriction in advanced cases of lipedema. Thus, the aim is to improve the patient’s mobility autonomy. When indicated, the liposuction to be performed is vibrosuction, with generous local anesthetic tumescence.

New laser technologies, including those aimed at liposuction, can help with results, not only aesthetically, but functionally, as, in addition to reducing local volume, there are improvements in mobility, local metabolism and sagging. The purpose of the laser is to act selectively on the fat, making it liquefied, in addition to retracting the skin by stimulating collagen through the emission of local heat. It is important to point out that extreme caution is required to avoid excess heat during the procedure in order to avoid worsening inflammation and the formation of cicatricial fibroses.

Other technologies, such as microfocused ultrasound, radiofrequency needling, isolated radiofrequencies, electrostimulation, endermotherapy and drainage can help in the treatment and control of lipedema, being indicated individually according to the stage of the disease.

For surgical treatment of fibroses related to lipedema, their detachment may be indicated. In this case, my experience has been the association of techniques known as Goldincision®. When the patient has low levels of inflammation, that is, the disease has been compensated, residual fibroses – often in great numbers – can be treated with collagen biostimulation and rupture of the fibrous septa via Goldincision®. Biostimulation, as discussed in more depth in another chapter of this book, is carried out by the application of microparticles

that, in addition to stimulating tissue collagen deposition, promote neovascularization, thus improving metabolism and tissue hypoxia. Local fat is decompressed by rupturing the fibrous septa with the Goldincision® method.

Lastly, good sleep, good bowel function and stress management are crucial to improving lipedema. All these aspects act in the treatment of inflammation and in its prevention.

CONCLUSION

Lipedema is a chronic inflammatory vascular disease that was first described a long time ago, but which has only recently gained greater recognition. Although few professionals have specialized in diagnosing and treating it, as a chronic vascular disease, it must be treated by vascular physicians, as they are the professionals trained to do so.

I have been treating lipedema for some time and I know how women who suffer from this disease feel guilty and anguished. I even had cases of women who, when unable to reduce down the bodily symptoms of lipedema, were judged and treated as liars. Because they do not have a correct diagnosis, which must be provided by vascular doctors who are familiar with the disease, women with lipedema often do not get positive results when trying to improve the aspects resulting from this disease, being subjected to treatments with admittedly inefficient techniques.

New approaches such as Goldincision® and new technologies have been advancing towards increasingly better results in the treatment of lipedema.

REFERENCES

Allen EU, Hines EA Jr. Lipedema of the legs. A syndrome characterized by fat legs and orthostatic edema. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin 1940; 15:184-7

Allen EV, Hines EA, Hines EA. Lipedema of the legs: a syndrome characterized by fat legs and orthostatic edema. Proc Staff Meet Mayo Clin. 1940; 15:184-7.

Amato ACM, Amato FCM, Amato JLS, Benitti DA. Lipedema prevalence and risk factors in Brazil. J Vasc Bras. 2022.

Bano G, Mansour S, Brice G, Ostergaard P; Mortimer OS, Jeffery S, Nussey, mutação S. Pit-1 e lipoedema em uma família. Exp. Clin. Endocrinol. Diabetes 2010, 118, 377-380.

Chen SG, Hsu SD, Chen TM, Wang HJ. Painful fat syndrome in a male patient. Br J Plast Surg 2004; 57:282-6.

Cornely ME. Lipedema and lymphatic edema. In: Shiffman MA, Di Giuseppe A, eds. Liposuction. Principles and Practice. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag; 2006.

Crescenzi R, Mahany HB, Lants SK, Wang P, Donahue MJ, Marton A, Titze J, Donahue PMC, Beckman JA Tissue. O teor de sódio é elevado na pele e no tecido adiposo subcutâneo em mulheres com lipedema. Obesidade 2018; 26, 310-317.

Criança, AH, Gordon KD, Sharpe P, Brice G, Ostergaard P, Jeffery S, Mortimer OS. Lipedema: Uma condição hereditária. Sou. J. Med. Genet. A 2010; 152A: 970-976.

Dayan E, Kim JN, Smith ML, Seo CA, Damstra RJ, Schmeller W, et al. Lipedema: the disease they call FAT. Cambridge: Lipedema Simplified LLC; 2017.

Dudek JE, Białaszek W, Gabriel M. Quality of life, its factors, and sociodemographic characteristics of Polish women with lipedema. BMC Womens Health. 2021; 21(1):27. ht t p://d x . doi .or g /10.1186/s12905- 021- 01174 -y. PMid:33446179.

Fife CE, Carter MJ. Lymphedema in the morbidly obese patient: unique challenges in a unique population. Ostomy Wound Manage 2008; 54:44-56.

Fife CE, Carter MJ. Lymphoedema in bariatric patients: chicken or egg? J Lymphoedema 2009; 4:29-37

Fife CE, Maus EA, Carter MJ. Lipedema: a frequently misdiagnosed and misunderstood fatty deposition syndrome. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2010; 23(2):81-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01. ASW.0000363503.92360.91.PMid:20087075.

Foldi E e Foldi M. Lipedema. In: Foldi M, Foldi E (eds). Foldi’s Textbook of Lymphology. 2nd ed. Munich, Germany: Elsevier; 2006: 417-27.

Földi M, Földi E, editors. Földi’s textbook of lymphology for physicians and lymphedema therapists. 3rded. München: Urban & Fischer; 2012

Frank RN. Vascular endothelial growth factorVits role in retinal vascular proliferation. N Engl J Med 1994; 331:1519-20.

Gavin KM, Cooper EE, Hickner RC. O conteúdo de proteína do receptor de estrogênio é diferente no tecido adiposo subcutâneo abdominal do que no glúteo de mulheres pré-menopáusicas com sobrepeso a obesidade. Metabolismo 2013, 62, 1180-1188.

Gregl A. Lipedema [in German]. Z Lymphol 1987; 11:41-3.

Harwood CA, Bull RH, Evans J, Mortimer PS. Lymphatic and venous function in lipoedema. Br J Dermatol 1996; 134:1-6.

Harwood CA, Bull RH, Evans J, Mortimer PS. Lymphatic and venous function in lipoedema. Br J Dermatol 1996; 134:1-6.

Helyer LK, Varnic M, Le LW, McCready D. Obesity is a risk factor for developing postoperative lymphedema in breast cancer patients. Breast J. 2010; 16(1):48–54.

Herbst KL, Mirkovskaya L, Bharhagava A, Chava Y, CHT Te. Lipedema fat and signs and symptoms of illness, increase with advancing stage. Arch Med 2015; 7: 10.

Herbst KL. Distúrbios adiposos raros (RADs) disfarçados de obesidade. Acta. Pharmacol. Pecado. 2012; 33, 155-172.

Herbst KL. Rare adipose disorders (RADs) masquerading as obesity; 2012 Feb; 33(2):155-72

Herbst, KL Distúrbios adiposos raros (RADs) disfarçados de obesidade. Acta. Pharmacol. Pecado. 2012, 33, 155-172.

Herpertz U. Range of lipedema at a special clinic for lymphological diseases: manifestations, combinations, and treatment possibilities [in German]. Vasomed 1997; 9: 301-7.

Hild AH, Gordon KD, Sharpe P, Brice G, Ostergaard P, Jeffery S, et al. Lipedema: an inherited condition. Am J Med Genet A. 2010; 152A(4):970–6.

Knudsen LS, Klarlund M, Skjdt H, et al. Biomarkers of inflammation in patients with unclassified polyarthritis and early rheumatoid arthritis. Relationship to disease activity and radiographic outcome. J Rheumatol 2008; 35:1277-87.

Langendoen SI, Habbema L, Nijsten TE, Neumann HA. Lipoedema: from clinical presentation to therapy. A review of the literature. Br J Dermatol 2009; 161:980-6.

Mayes JS, Watson GH. Direct effects of sex steroid hormones on adipose tissues and obesity. Obes Rev 2004; 5: 197-216

Meier-Vollrath I, Schmeller W. LipoedemaVcurrent status, new perspectives [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2004; 2:181-6.

Meier-Vollrath I, Schmeller W. LipoedemaVcurrent status, new perspectives [in German]. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 2004; 2:181-6

Michelini S, Chiurazzi P, Marinho V, Dell’Orco D, Manara E, Baglivo M, Fiorentino A, Maltês PE, Pinelli M, Herbst KL. Aldo-ceto redutase 1C1 (AKR1C1) como o primeiro gene mutado em uma família com lipedema primário não sindrômico. Int. J. Mol. Sci.2020; 21:6264.

Ourke JH, Langford RM, White PD. The common link between functional somatic syndromes may becentral sensitisation. J Psychosom Res. 2015; 78(3):228–36.

Reich-Schupke S, Schmeller W, Brauer WJ, Cornely ME, Faerber G, Ludwig M, Lulay G, Miller A, Rapprich S, Richter DF, Schacht V, Schrader K, Stücker M. and Ure C. S1 guidelines: Lipedema. JDDG: Journal der Deutschen Dermatologischen Gesellschaft, 2017; 15:758-767. https://doi.org/10.1111/ddg.13036.

Rudkin GH, Miller TA. Lipedema: a clinical entity distinct from lymphedema. Plast Reconstr Surg 1994; 94:841-9.

Schmeller W, Meier-Vollrath I. Pain in lipedemaVan approach. LymphForsch 2008; 12: 7-11.

Schwahn-Schreiber C, Marshall M. Prävalenz des Lipödems bei berufstätigen Frauen in Deutschland. Phlebologie. 2011;40 (03):127-34. http://dx.doi.org/10.1055/s-0037-1621766.

Shin BW, Sim YJ, Jeong HJ, Kim GC. Lipedema, a rare disease. Ann Rehabil Med 2011; 35: 922-927.

Stutz JJ, Krahl D. Water jet-assisted liposuction for patients with lipoedema: histologic and immunohistologic analysis of the aspirates of 30 lipoedema patients. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2009; 33:153-62.

Suga H, Arakai J, Aoi N, Kato H, Higashino T, Yoshimura K. Adipose tissue remodeling in lipedema: adipocyte death and concurrent regeneration. J Cutan Pathol 2009; 36: 1293-8.

Suga H, Arakai J, Aoi N, Kato H, Higashino T, Yoshimura K. Adipose tissue remodeling in lipedema: adipocyte death and concurrent regeneration. J Cutan Pathol 2009; 36:1293-8.

Szél E, Kemény L, Groma G, Szolnoky G. Pathophysiological dilemmas of lipedema. Med Hypotheses.2014; 83(5):599–606

Szolnoky G, Nagy N, Kova ́ cs RK, et al. Complex decongestive physiotherapy decreases capillary fragility in lipedema. Lymphology 2008; 41:161-6.

Van Pelt RE, Gozansky WS, Hickner RC, Schwartz RS, Kohrt WM. Modulação aguda da lipólise do tecido adiposo por estrogênios intravenosos. Obes. (Silver Spring) 2006, 14, 2163-2172.

Wold LE, Hines EA Jr, Allen EV. Lipedema of the legs: a syndrome characterized by fat legs and edema. Ann Intern Med 1951; 34:1243-50.

Wold LE, Hines EA Jr, Allen EV. Lipedema of the legs: a syndrome characterized by fat legs and edema. Ann Intern Med 1951; 34:1243-50.

Wold LE, Hines EA Jr, Allen EV. Lipedema of the legs: a syndrome characterized by fat legs and edema. Ann Intern Med 1951; 34:1243-50.

Woodliffe JM, Ormerod JOM, Beale A, Ramcharitar S. An under-diagnosed cause of leg swelling. BMJCase Rep. 2013.

Zhao J, Hu J, Cai J, Yang X, Yang Z. Vascular endothelial growth factor expression in serum of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Chin Med J (Engl) 2003; 116: 772-6.